Thirty-Nine

I

This year I am turning thirty-nine years old — the same age as my father when he died.

There are few fair and impartial arbiters in life: time is one of them. Regardless of your feelings, how much money you have (or do not have), and precisely how good of a person you are, time still charges forward with little regard to you personally. In some ways, this is a relief. Knowing that all things must pass in time is the old stoic's way of enduring hardship. But in others, time creeps up on you like a bandit in the night.

Most birthdays after twenty-one are just numbers — forty, sixty-five, maybe a hundred if you’re lucky.

There are very few dedicated birthday cards for thirty-nine.

And none of them say, “Congrats, you're as old as your old man ever was.”

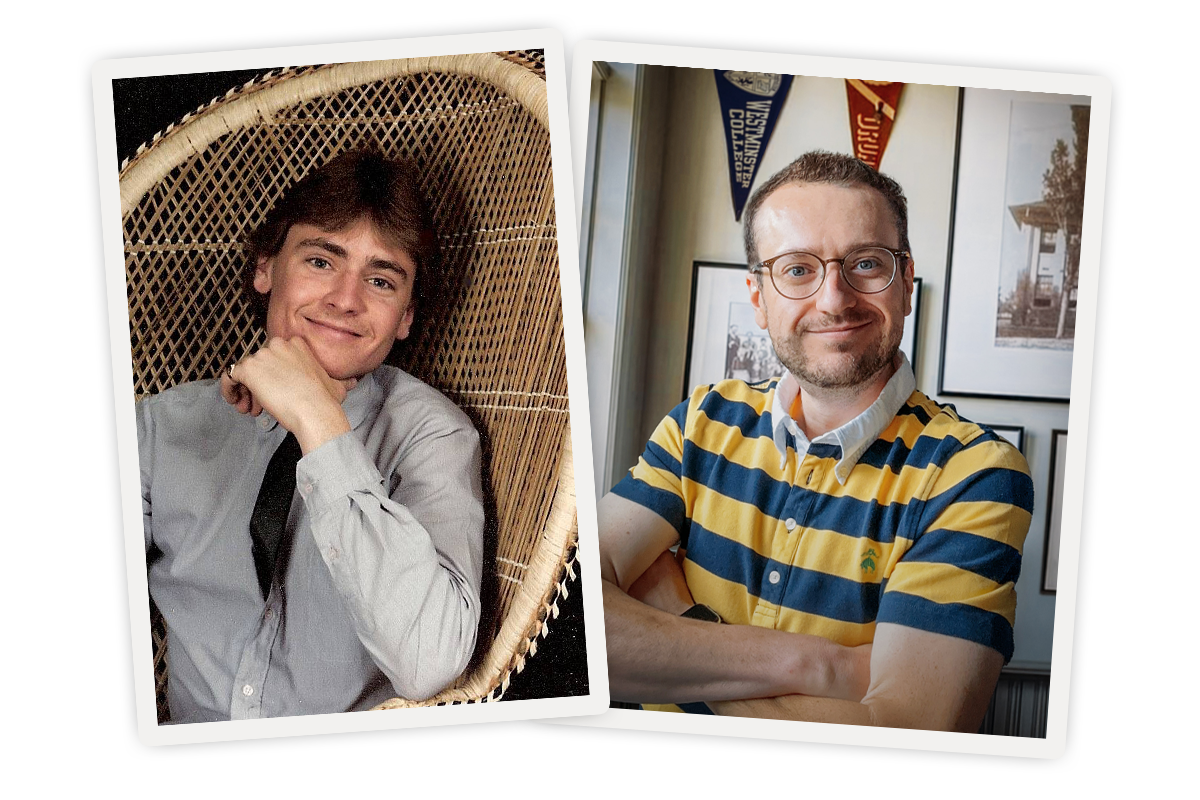

In my case, thirty-nine feels less like a birthday and more like a monolith. It's less an age than an opened door into a darkened and unfamiliar house where you can't quite see the interior. The furniture appears to be covered, thick swirling dust is visible through what little light streams from the exterior, and the only thing you can see, that you can really clearly see, is a mirror a few steps beyond the threshold, reflecting more than just myself. I can see myself in it, the familiar wrinkles and laugh lines and the silhouette of my shoulders and my waist, but there's a second person in the mirror behind me. I'm not the only visitor to this particular house. His jawline and cheekbones and the creases around his eyes look a little too familiar. It's not a perfect match — more like a bad double exposure, two images printed on the same negative. He's the ghost in my reflection.

For the last few years, I've been thinking about this number in the same way that the perpetually stoned, free-wheeling girl in your high school graduating class thought about constellations: heavy with meaning, portents, and omens. Thirty-nine has a sort of gravity to it. It's not a number that you enjoy; it's the number written on your dead dad's death certificate and, this year, the number on my birthday cake. The 3 and the 9 feel like road signage, the kind you encounter late at night driving cross country with your headlights carving out beams of clarity, and suddenly you see the signage on the shoulder and realize that you've never been on this road before. For a brief moment, you are hit with the flickering idea that you have no idea where you're going or what might be on the other side of that sign. Of course, you logically know that there's the same thing on one side of the sign as the other: more road. But in that brief instant of unfamiliarity, you're filled with the dread of uncertainty. I'm not sure, exactly, where I am. And I'm sure I'll be fine. But where, exactly, am I?

I am, at heart, a romantic, although I know better than to romanticize this as fate. I firmly believe that fate is what you make of it, and while many things are predetermined outside of your control, they're more about the world you've been born into and the social factors at play than some grand cosmic blueprint. Numbers aren't killers in this case. The symmetry of faces isn't prophecy. But both still rattle me to some extent. There's a sort of undesired intimacy in it, the sharing of an outline of years, to step into someone's final footsteps and realize that yours will be the only boot prints in the dust going forward.

Thirty-nine is an appointment I never set, but I still showed up, right on time.

II

Troy P. Hudson was, the obituary begins, a “Husband, Father, Son, Brother, and Friend to All.” This is entirely correct, but it (and the rest of the obituary) somewhat misses the bigger idea: the man was positively luminous.

In thinking about him, I'm hard pressed to identify any enemies, or even any low-grade foes, that my father may have had. It's a well worn cliché to say, when discussing any deceased person, that they were universally loved and had nothing but friends, although I suspect that it's probably true in my father's case. He had the kind of presence that universally made rooms a little lighter. His sense of humor was goofy but mostly gentle, generous and self-effacing and inclusive. He laughed easily and quickly, often at childish things, and did so in such a way that his friends and peers were encouraged to laugh alongside him. He loved encouraging people to be happy, and to have a good time. In his early twenties, family lore goes that he spent a decent amount of time DJing at local clubs, which would explain the prodigious record collection he left behind for me. It makes sense, in a way — the idea of him presiding over a party is entirely in character with the man I knew. No fewer than three separate people approached me at his funeral and announced, unprompted, that my father was “the nicest guy you’d ever meet.” Normally, that would be exactly the sort of description you’d instantly distrust, but here it was true. This was a man who, just weeks after his death, had his work office gently ransacked. When they found the culprit, it turned out to be a quiet, mild-mannered guy that my father had managed who was, believe it or not, looking for a sentimental keepsake of my father that he was afraid to ask one of us for. The grand total value of his attempted theft was somewhere in the range of $10.

At the dealership, “Service Manager” was his title. He took it literally: to be of service, to make sure every interaction left people a little better than when they arrived. The car industry’s reputation was for dishonesty; his was for fairness.

This was, of course, all in service of my mother. Their marriage was turbulent in the way that all marriages over a period of time are, but there was never a point at which I questioned his commitment to her or to our family. He worked hard, almost obsessively so, but typically in the pursuit of “more.” More for her, more for us, and more for himself by extension. If the American Dream is doing better than your parents did, his full time preoccupation was in making sure that it happened. And it did.

Over time, however, this became a trap. At a certain point, the desire to do better, to earn more, and simply to have more became a self-perpetuating cycle — and at the height of his life, in the middle of that accumulation, the cancer arrived. Suddenly “more” becomes less of a thing you want and more of a millstone around your neck. Work for the sake of success becomes moments away from self-care, or from your family. The circle widens and cannot hold. You can work your way out of many things in life, but a terminal illness is not one of them, and all the long hours, the commitments, the dedication to service, none of that changes the cruel biology of life. Eventually time runs out. The friendly and quick smile becomes thinner, and eventually skeletal. The familiar goatee and facial hair becomes thin, and then disappears entirely. The laugh lines are replaced by regular lines, and then deep crevices. His legs stopped working, and now it was a full time wheelchair, and constructing ramshackle ramps to get in and out of the house.

“You can buy a new car, but you can't buy a new day,” someone told him once when he returned to work in the midst of the illness. It's common for men, terminally ill and sensing their end is coming, to reach a stage at which they try to return to normalcy, to try and go back to work with the idea that repeating their old behaviors might lead to their old lives, as if the reaper can be tricked by the camouflage of familiarity. It lasted a few days, and then he got sicker.

III

I was not the son he expected, or — stated with the certainty of adulthood and strong self-awareness — the son he wanted.

My father was athletic. He had been a high-school jock, thin and wiry but strong and muscular, a reliable hand on both the hockey and baseball teams, both in and out of school. He once suffered a legendary injury during a hockey game, when the bone beneath his eye socket shattered and his eyeball slipped down into his face. He calmly went home, washed a spoon in the kitchen, slid it under his eyeball through the spattering of bone, and held his eye up long enough to go to the hospital. He was self-assured and confident and handsome, good at sports, quick with a joke, easy in his own body. He moved through the world as if his presence simply made sense there.

I was none of those things. I was heavy, awkward, bookish — more at home in stories and trivia than in sports or games. I don’t think I ever saw him read a book, while I was never without one. He embodied ease and competition; I embodied the opposite. We lived in different worlds, and the view from each was strange and untrustworthy.

When I was eight or nine, my father launched a crusade to find “my sport.” To his understanding, the problem wasn't that I was a quiet, nerdy, vaguely flamboyant child... it was that I simply hadn't found “my sport” yet, the athletic activity that would release me from the dorky chrysalis of boyhood and allow me to emerge as a masculine butterfly. The idea was ludicrous, of course. One of my mother's favorite early memories of me is when I was maybe five or six years old, sitting on the front porch of our house in cleanly pressed shorts and an immaculate little polo shirt, watching the other neighborhood children play.

“Why aren't you playing with them,” she asked, nervous that I had been excluded or bullied.

“They asked me to,” I replied, “but I'd rather sit here, I don't want to get my clothes dirty.”

Such was the Herculean task my father was faced with, the Sisyphean struggle to overcome natural temperament to create the son you'd prefer.

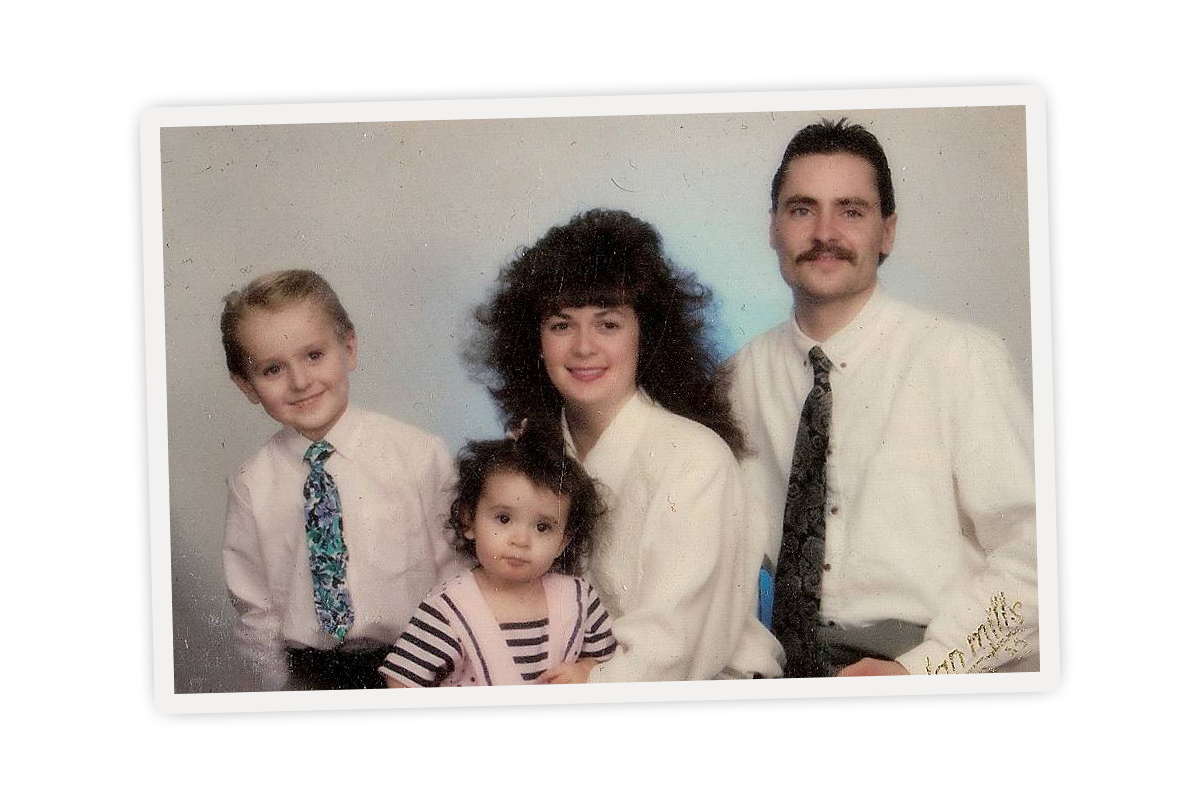

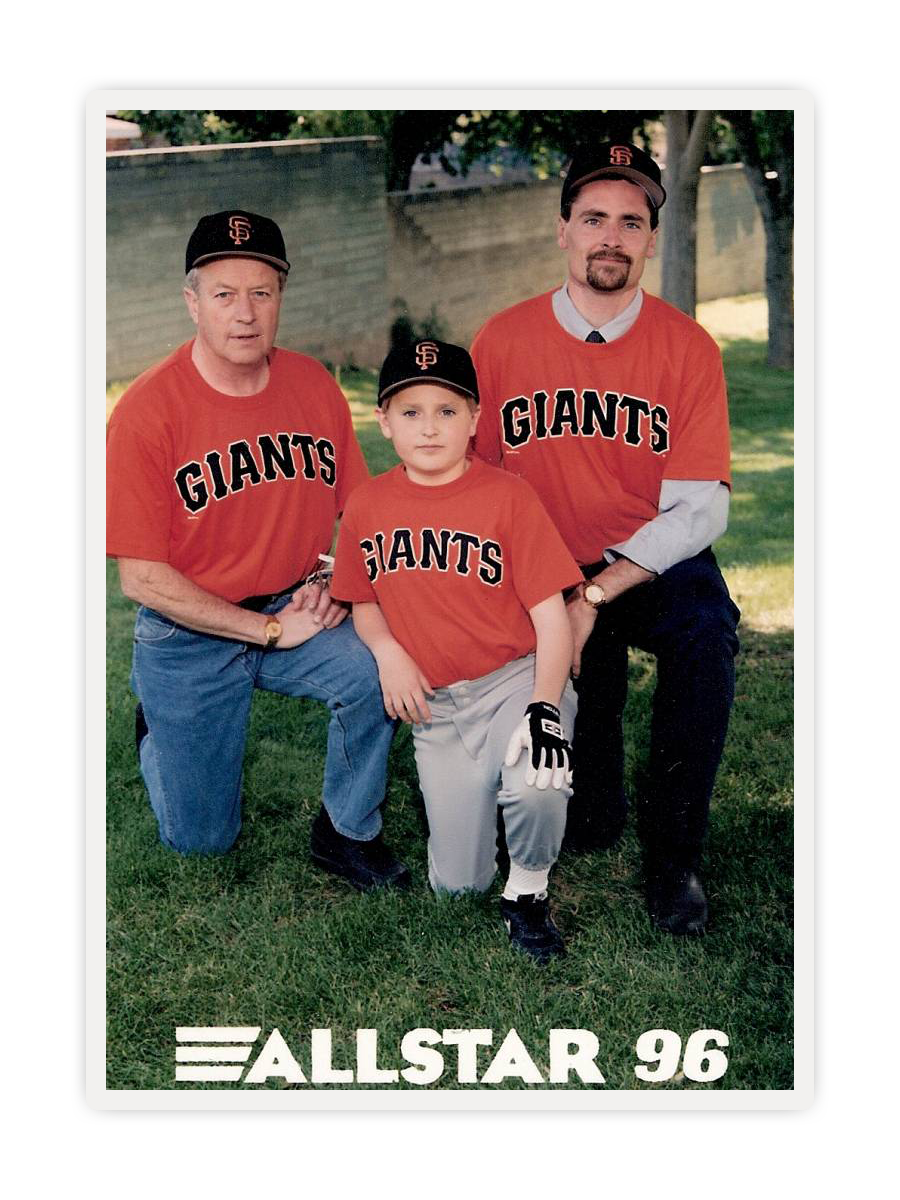

I was drafted into soccer, then basketball, then Little League baseball. My dad and grandfather even coached the team to guarantee I showed up. There’s a photo of us together in uniform — his smile says everything, mine says something else entirely. His pride is obvious, my worry about grass stains just as obvious. When baseball failed, he moved me into karate. That fizzled too.

In time, we reached an uneasy truce. He stopped asking me to throw a ball; I stopped telling him about movies and stories. We coexisted as strangers on the road but family by blood. If there was a wound, it was not that he did not love me. I know he did. The wound was the lingering suspicion that he didn't like me. And that distinction is an important but brutal one.

Love is a duty; liking is a choice.

And what child doesn't want to be chosen?

As an adult, I can't fault him. I know he was trying. I recognize the signs every time I have tried to connect with the child of a friend, or someone twenty or thirty years younger than myself. We all want to pass something down to a newer generation while being faced with the brutal reality that we very likely do not inhabit the same world. He wanted me to inherit his world, his ease in his body, the camaraderie he found in team sports, the confidence that allowed him to bluster through rooms and into relationships. He wanted me to be a part of his lineage, to be the model son and the miniature replica, and not... whatever I was to him. I was the boy who felt more at home in a library than a locker room, with soft hands and a thick stomach and the sporting prowess that meant I was never picked first, or was often not picked at all. My awkwardness but purity of self was a shield, and his expectations were a sword. The clash was quiet but constant.

Of course, time has a way of making fools of us all. The irony — true, cruel irony, the kind that the ancient Greeks loved so much — is that as I've grown older, I've turned more into him than I would have ever imagined. We all become our parents to some extent; the science says we're half biology and half our environment, and the vast majority of adults in the world are a reflection of, or a reaction against, the people who raised them. I've accidentally turned into the former.

I'm more athletic now as an adult. I jog and I row and I lift weights with the level of discipline that a younger version of me would have scoffed at and dismissed as simple minded or foolish. As the weight has left my body, I'm left with a frame and a facial structure that looks uncomfortably close to his, where one of the first compliments I receive from anyone who hasn't seen me in years is that I look a lot like my father. The confidence in my own body has made me more at ease and more comfortable in every room I walk into. I've always been complimented as kind and likable, but now the compliments come more frequently, and feel more genuine. They echo the things I heard about him as a kid, in his work, in our neighborhood, and over his casket. That's the true sting of time — in his absence I became more like him than I would have in his presence. My arrival was only possible through his departure. This was the strange inheritance I received from my father. It wasn’t money or resources — those disappeared into medical debt immediately after his death. Instead, my gift was to grow into the mold of someone who never was able to see it happen. To embody the best of what he was, and the best of what I was capable of, long after the chance for recognition had vanished.

This legacy is paradoxical. As a child I resented the pressure of his expectations, but those same expectations are my reality now. I grieve the distance between us but carry his likeness in the mirror. I was loved but not liked, and now the ways that I am liked are in ways that mirror how he was liked. It's an uneasy question, what he might think now, should he see me. Would he laugh and pat me on the back, satisfied that I had become the thing he always wanted? Would he recognize the child in me nestled inside the man I became? Would he be comfortable in the overlap we finally found?

Ultimately, does any of it matter?

IV

I was seventeen when my father died, which is an unfortunate age to lose a parent. Old enough to understand the gravity of what was happening — and just how significantly life was about to change — but not old enough to carry the weight gracefully.

But cancer never arrives welcomed, and never arrives at a convenient time. It crept into our home like a trespasser and set up shop, occupying corners and odd spaces until it could overtake rooms and hallways. With it came the familiar signs of a serious illness in a house with children: the stilted conversations that end abruptly when someone enters the room, the phone calls that are a little too quiet, and the medications that are stored in drawers no one thinks to open. Initially it seemed like something of an abstract. Cancer happens to people, sure, but not to people in their mid-thirties. Not to people who are so healthy and active, to people who are so central to the lives of so many other people, to family men who have families to care for, young families, families who live in houses with bills to be paid and vacations to take and retirements to plan for. Cancer happens in quiet hospital rooms that smell like sharp chemicals, to people who have had full lives and are now spending their final years watching game shows and complaining about the weather. It doesn't happen in the middle of your life.

Until it does.

It's hard to identify what was the definite first sign that things were going off the rails. It might have been when, at the hospital in Anaheim (we were on vacation when the first symptoms hit), the doctors told him he was too sick to get on an airplane and they would not medically clear him to fly. He flew home anyway. It could have been when he was admitted locally, and was hallucinating that my mother was a terrifying bird-woman with wide wings and a sharp beak, trying to kill him. It might have been after the third or fourth or fifth scan, or the way that the pronouncements from hospital staff became less routine and flippant, and more patient and cautious. But at some point, it became apparent that the metaphorical ticket had been purchased and the ride was going to be taken.

Hospitals became too familiar. The sour smell of chemotherapy is one you can’t quite remember, but can never forget. And soon, those smells and sounds began to bleed into our home.

When he was allowed to go home, ostensibly for palliative care, the house became rearranged and the atmosphere shifted. So did his body. His laugh, which previously would have filled up the room, became lighter and whisper. Like his hair, his broad shoulders thinned. He joked still, but the jokes seemed as tired as he was, half-finished and weary. My mother kept the routine going with the normal rhythm of family life — dinner and chores and social activities — but the weight was always there, carried like an invisible and unspoken backpack, weighing every decision and action into a calculated risk. Can we make it to the grocery store and back? Yes. Could he make it through a movie in the theater? No.

I felt myself slowly falling into a role I wasn't prepared for: the de facto “man of the house.” It wasn't a title that was given to me — even at his sickest, my father was too proud to acquiesce that away. But mentally I started to prepare myself for the expectation, typically unspoken but sometimes stated plainly by a well-intentioned relative or family friend who thought that perhaps I, a teenage boy, hadn't grasped just how badly it would be should one of my parents spontaneously die. Seventeen is still a child, and I was a child: awkward, scared, and unprepared, but publicly wearing the mask of responsibility. When my teachers at school would ask how I was doing, I would tell them that things were difficult but I was fine, proudly flying the agreed upon family flag of unity and strength despite what may be happening behind closed doors. It was hard, sure, but I was a man. I had to be strong for my mother and my sister, and to start shouldering the weights my father could not hold.

I was terrified.

And I kept most of it to myself. Friends, teachers, extended family, everyone made themselves available to listen, but never in a way that felt particularly helpful. People like the idea of supporting people in crisis; very few people actually find the strength to do so. Everyone wants to hear how your day is going, but nobody wants to hear much beyond, “Good, and yours?” So I allowed the weight to settle and harden like concrete. By the time he died, the concrete cured. And, as expected, the world didn't stop the way that we sometimes imagine in our head that it will. It keeps moving with the predictable and offensive normalcy of life. Strangers told me what a great man my father was, and how I would one day become like him. I accepted the words, packed them away to process some other time, and went about the required routine that follows a death in the family. There was little time to grieve a father I didn't understand and who didn't understand me.

This silence has lasted years. Point of fact: this essay, what you're reading right now, is the most extensively I've ever talked about this, with any single person, ever. You're currently in the most in-depth monologue about a parent dying that I've ever delivered. If you didn't understand what you were getting into within a paragraph or two, that's on you, not on me. A lot of the conversations we have about grief and aging are really conversations about logistics — how things happened or are going to happen, what it's literally like in the exact moment, what your plans for the future are. The actual rawness of understanding comes separately, over time, and isn't usually expressed until there's some compelling reason to address them. Like, say, turning thirty-nine.

I've matured inside that silence and been shaped by it, allowing resilience and loneliness to give way to understanding and peace. And now, this feels like a field test of the end result. My birthday, and my father's birthday, were only a few days apart. In early December of this year, I will have lived longer than my father did. We're headed off the map and into uncharted territory. Here there be tygers.

V

In just a few days, I'll be his age. Which is unusual in a way I can't quite put my finger on. For decades, I've carried this imaginary idea of my father's death age like a ceiling, a mental cap somewhere in the back of my imagination. I've never explicitly thought, “Oh, I'm going to die when he did.” Although, that's not true, now that I think about it. It was a very real thought when I was diagnosed with my brain tumor a few years ago. But that felt different, in the same way that any surprise illness makes you grapple with your own mortality. This is a different kind of signpost. I think on some level, there's always been some assumption deep inside of me about how long my adulthood would last, and thirty-nine was the unspoken cap. Every year since seventeen, I've been inching towards it, slowly but surely, thinking that it may arrive and I would find myself erased by some random fluke chance. I beat the brain tumor, sure, but nobody beats the odds forever. There's always car wrecks. Poisoning from a deadly enemy. An engine falls off a jet plane and lands in your house, killing you in bed. Stranger things happen every day.

And yet, as I draw increasingly closer to the day, I find a new confidence that maybe the ceiling isn't a solid one. Maybe the structure is less Douglas fir and more balsa, the ceiling less stone and more acoustical tile. Soon enough I'll be able to push through, into something big and unknown — a thirty-ninth year not defined by ending, but by beginning. It’s eerie, stepping past a boundary my father barely crossed. I’m stepping into the life he never mapped.

Thirty-nine is the year where his story ended, and where my story is allowed to continue. A part of me foolishly views it as a betrayal, but it's not. To survive is a noble fight, and to carry on beyond where he was allowed to serves as a form of continuation. Every day past thirty-nine carries a little more weight, because each one is a day that life — chaotic, unpredictable, cruel, awful, beautiful, and wonderful — just keeps going. And so this is the year I'm allowed to go forward. As an adult, I've spent a lot of time attempting to understand my father, and my complicated relationship with him. I like to imagine that I've learned to give myself a little grace, and to be able to extend my compassion backwards to a seventeen-year-old who thought that silence was strength. I hope that I can extend my compassion forwards, too, to my father, not as “dad,” but as a man. A man with flaws, limits, desires, and expectations. A man whose time was cut short before he could finish becoming whoever he was meant to be, a luxury which I now get to enjoy.

In the end, this birthday is not a triumph, but an understanding, and a reckoning. If he was stopped arbitrarily at the great dark door through which I'm about to enter, I will enter it with my head held high and walk into the murky unknown. The great house that is the my future need not be quite so frightening, for ultimately, this house is mine. I will curate these halls, decorate these walls, and dash madly from room to room throwing curtains aside and flipping on all the lights.

The mirror is still there, and the reflection continues to age. This is the year we finally see what that Hudson smile looks like at forty, if everything goes according to plan.

Thirty-nine is not a broken clock, and it's not a stop sign.

Thirty-nine is a record on the turntable and a tall, cool drink waiting in the fridge.

I wonder what the music sounds like.

Let's find out.

Published August 28th, 2025.

As of publication,

Austin is still alive.